|

| A LIFE REDEEMED A heroin addict credits Maine's new drug court program for transforming her life. SUN JOURNAL Lewiston, Maine Sunday, September 10, 2000 Linda Ball's pink, purple and white sweet pea blossoms are her weapons against the longings she still feels for heroin, cocaine, pain pills and a Budweiser with her morning coffee. In the two years that drugs have been out of her body, she has planted her first garden. Pumpkins, bachelor's buttons and morning glories grow along with the sweet peas.

And she has made two lists. It is obvious which is better, yet the old yearning for the relief drugs and drink can bring pulls at her still. Heroin was smooth and euphoric. She'd do her job cleaning houses, thinking, "Yippee. I get to go to work." Nothing would bother her. That was until it stopped working. Then heroin just made her numb, the way the other drugs did. She didn't choose her life in those days. Things just happened. For 15 years, she didn't know she had the disease of addiction. She didn't think she was an addict. Desire and dependency ruled her, making her live life in two parts. The drug part, which demanded that she stay high on something all the time, and the denial part, where she would go, go, go, pretending everything was fine. She found an all-night Laundromat so she could wash her clothes in the middle of the night. She coached her son's T-ball team. As a room parent for his class, she'd get record numbers of people to show up for school activities because she kept them on the phone until they gave her a yes or no answer. She knew she wasn't an addict because she could switch between drugs. You can quit, she'd tell herself as she walked to the store in the morning to get more beer. You can quit. But she didn't quit until a year and a half ago, when she was 35 and a judge sent her to jail minutes after the assistant district attorney smelled alcohol on her breath. The swift sanction was part of a federally funded program aimed at getting addicts off drugs and reducing drug crimes. In Maine, the pilot drug-court program Ball had enrolled in ended in the summer of 1999, but state funding has been approved for drug courts in four counties, including Androscoggin. By the time the pilot program ended, Ball was one of the 35 who had graduated, outlasting 24 others who were expelled. "I probably would be in jail or dead if it wasn't for the adult drug court," Ball says.

Sipping Jim Beam As a girl she'd sneak sips from her father's jug of Jim Beam for that nice relaxing feeling. After she married her husband, a fisherman, they shot up needles of the heroin he'd bring home on his boat. When he was gone for weeks, she'd drink; when he came home they'd do drugs. Once she remembers flopping around on the floor with convulsions from too much cocaine. "It just went on like that for so many years," she said. Her job as a self-employed house cleaner let her get away with the bad days. She was the queen of rescheduling. "The bills were paid, but barely," Ball said. "Your mind tells you it wasn't that bad, but emotionally and spiritually you're just an empty shell." She'd go through spells with heroin. After six months, and hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of dollars, she'd stop because she didn't feel high. Alcohol was more constant. She'd get up and promise this would be the day she'd go without. Within 15 minutes, she'd be up at the store, buying a couple of cans. The true end began during a drug bust when police caught her climbing out a bathroom window in Rockland. With handcuffs on behind her back, she tried to wipe off the blood that ran down her arms from the needle. She'd been injecting some celebratory heroin for her 34th birthday. Her ex had offered to treat her for the occasion and she couldn't resist the freebie. Police tested the empty bag she was holding as she tried to escape and found heroin. For the first time in her life, Ball was arrested for drugs. That wasn't enough to get her to stop, however. She received no jail time, and spent a year on probation, drinking and drugging and getting away with it. That ended after three days in an Old Orchard Beach motel room sucking on a crack pipe. She was missing an appointment with her probation officer and she didn't care. He went to her apartment and kicked in the door, thinking he'd find her dead.

The smell of alcohol The program would keep a closer watch on her. Ball was tested for drugs and alcohol three times a week, made daily phone checks and had weekly meetings with Judge Robert Crowley at the Cumberland County Courthouse in Portland. "It was the first time I really felt anyone cared about what happened to me," she said. After a year of probation, Ball's disease had allowed her to still believe she wasn't addicted to anything. But after one month of drug court, she started to change on the inside. At the weekly meetings, the judges, district attorneys, representatives from the Attorney General's Office, drug counselors and probation officers gathered in the court with Ball and the other people in the program to go over the week's progress. Listening to their stories, Ball became fond of some. She could always tell by looking at their faces whether they'd screwed up the week before. She knew from experience. Whenever she had used drugs, it showed on her face too. Circles under her eyes were black and her wrinkles more obvious. Judge Crowley would ask Ball how she was, how work was, how her son's football game was. "Everybody thought I was really getting it, but I really wasn't," Ball said. "I was in such denial it's amazing." After about a month, during one of the weekly court check-ins, she was near the assistant district attorney signing a paper. He smelled the leftover beer and Manhattans on her breath, forced her to take a Breathalyzer test and told her he was sending her to Cumberland County Jail.

"No," she said. She had just spent a week in jail the week before for the same thing.

A race from addiction If they set her free before then, they were afraid she'd get caught drinking again. Then they'd have no choice but to kick her out of the program. For two months Ball wore an orange convict suit and went to the required weekly drug court visits in shackles. She'd never been separated so long from her son before. He had gone to stay with his father and she was missing his birthday and she hated being away from him. Her probation officer came and told her if she was clean, she could be a better mother to her 11-year-old son. She remembers him asking, "What's six months of your life to have a lasting relationship with him?" All she did was cry and the guard kept coming up to her. Was there anything he could do? He moved her to a double cell with windows. Days passed and her head started to clear. She'd never stopped drinking long enough for that to happen before. Relief sank in. She knew it was over. A friend brought her some good sneakers and she started jogging. The guard said 20 laps around the gym was a mile. She did 20 laps every day. At the rehabilitation center she met with other women residents for group talks. One day they told her she was a workaholic, a kind of compliment. "I just laughed," she said. "I haven't achieved anything in 20 years but screw up my life. I could feel my mouth drop. That was just so foreign to me. I always thought I could not deal with stress." She'd been on drugs so long she didn't notice things about herself. At rehab, she learned about the chemistry and psychology of addiction. Her parents' history had predisposed her to this. A drink or a drug in her system triggered a physical compulsion for more and a mental obsession for more. "Normal people don't drink a beer and then go out of their mind," she said.

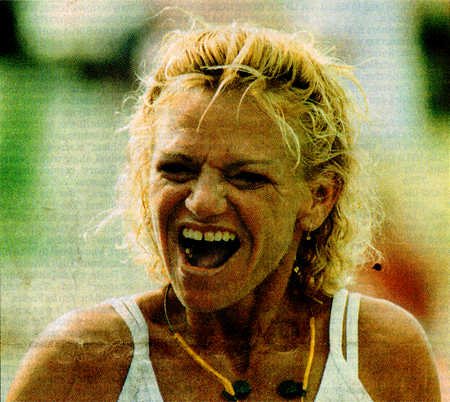

'Mamma I'm proud of you' "I agree," he said and cut the probation time to three months. His respect was a better high than any drug she'd ever had. When she walked out, her son wrapped his arms around her and said, "Mamma I'm proud of you." She got a scholarship from the District Attorney's Office for a semester at the University of Southern Maine. In her introduction to business class she managed a mock running shoe company and ranked first out of 193 students. "It was a relief to know that my brain still worked and I hadn't fried it completely," she said. She's an athlete now. The jogging she kept doing every day led to running competitions. She's finished three races so far. Each time she runs she studies the other runners, looking for Judge Crowley. She heard he ran too and she wants him to see her. |